The Armenian Ethnic Enclave of L.A.

June 1, 2022 - Inna Mirzoyan

MSU Sociology PhD student Inna Mirzoyan published this essay in Community & Urban Sociology

Inna Mirzoyan

Michigan State University

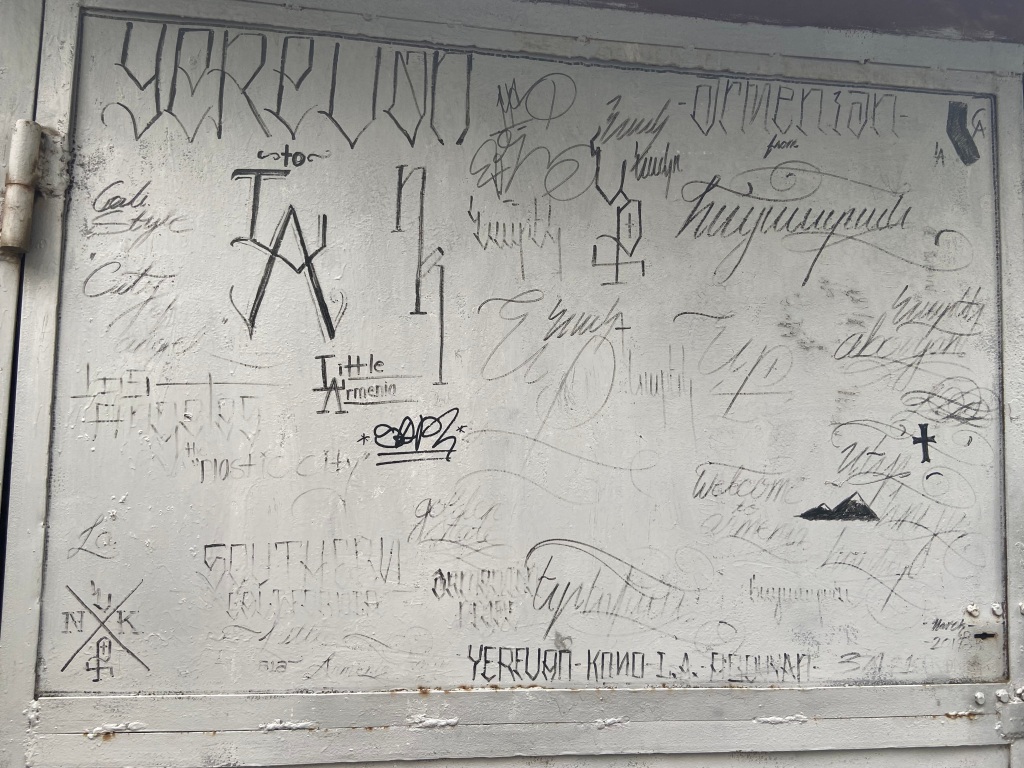

During one of my first weeks as a 2021 Fulbright researcher in Yerevan, Armenia, I explored the capital city’s oldest district, Kond. The Kond district and its ruins have been revitalized with street art and graffiti to attract locals and tourists alike. Immediately, the multiple references to Los Angeles stood out to me. Specifically, one large wall that I captured accurately reflected the transnational experience of the Armenian Diaspora with large text that read “Yerevan to L.A.” and “Little Armenia.” Six months later, in 2022, I traveled for my second phase of fieldwork in L.A. and saw a similar global conversation happening between diasporans and locals.

As an Armenian-American, I cannot remember a time when I did not hear about L.A., specifically Glendale, in relation to Armenians. Los Angeles is home to the largest Armenian-American population with most Armenians clustered in the City of Glendale. The Armenian history and impact is felt immediately when visiting Glendale. Here you will find Armenian flags on the outside of suburban homes, Armenian restaurants, pharmacies, coffee and floral shops, and groceries stores as reflected with the countless store fronts signs of establishments that include names like Armen’s, Ara’s, Sarkis’ or Lilit’s. However, Glendale was not always the Armenian ethnic enclave it is today.

The earliest settlement of Armenians in California was in the city of Fresno, just over a three-hour drive north of L.A. Around the 1870s, Armenians migrated for economic opportunities and became leaders in the agricultural sector and successful business owners in the area (Fittante 2017). Fresno eventually became home to several Armenian institutions such as churches, schools and community centers as a reflection of the city’s growing Armenian population. At the end of World War I, Fresno became a place of refuge for several Armenian Genocide survivors who escaped the Ottoman Empire in the early 1900s, contributing to another boom of Armenian activity in the area. Today, one can even find the Armenian Museum of Fresno that highlights this history. However, the Armenian settlement slowly shifted to Southern California, specifically L.A, due to the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, new waves of migration from global conflicts in long-established diaspora countries, such as Iran and Lebanon, and as Armenians sought out new business opportunities and became more successful.

When Armenians first began settling in L.A., it was East Hollywood that evolved into becoming known as Little Armenia, which received this official title in 2000. The Armenians of Hollywood established several small businesses, some of which are still present today, such as automotive shops and grocery stores. Armenian street art also exists in Hollywood with one of the most famous murals found on the corner of Hollywood Blvd and Winona on the wall of a local restaurant called Friends & Family. This mural, completed by a local Armenian graffiti artist, pays tribute to Armenian Genocide survivors as well as other countries who faced persecution reflected by the flags on the left-hand corner of the mural. The biggest part of this mural is of an individual with tape and the year 1915 around her mouth, highlighting the political relationship of the United States of America and Turkey that resulted in years of the U.S. never officially recognizing the Genocide to maintain desirable foreign relations with their allies. During these years, Armenian activism and the impact of diaspora organizations grew in L.A. and Washington, D.C. with organizations such as the Armenian National Committee of America, with offices in D.C. and Glendale, pushing members of Congress to sponsor legislation supporting not only the recognition of the Genocide but to increase foreign aid to Armenia and highlight the human rights violations and discriminatory practices of its adversaries on its borders (see Adar 2018; Paul 2007). It was not until last year, on April 24, 2021, when President Biden became the first sitting U.S. president to finally use the word “genocide” in his White House statement on the Genocide Remembrance Day.

Other similar remnants of Armenian life still exist around Hollywood. Not far from the Genocide mural is another mural next to an Armenian pharmacy. This mural shows the Statute of Liberty in the center with traditional Armenian symbols in the background including Mt. Ararat and an Armenian monastery. This mural illustrates the role the U.S. played in providing safe refuge for Genocide survivors. Walking down Hollywood Blvd. one can find the Nairi Banquet Hall, Hrach’s Hair Studio, Taron’s Bakery, and the Arbat Grocery and Deli. A few blocks away is the Pilibos Armenian School and the St. Garabed Armenian Church on N. Alexandria Ave.

Yet today, several Armenians in LA can be heard saying, “Glendale is Little Armenia” since Hollywood experienced a demographic shift and Armenians left the area in large numbers by the 1980s after improving their socioeconomic status. It does not take long to see a difference between East Hollywood and Glendale which encapsulates the traditional immigrant story of upward mobility. While Glendale includes several older apartment complexes, including subsided housing for elder Armenians and new immigrants who lack English speaking skills, it is increasingly becoming an area with high real estate costs in its suburban neighborhoods.

Almost immediately upon entering Glendale, you can find Armenian influence and not only in Armenian establishments. The Armenian language is heard while walking around Glendale’s Americana, developed by current L.A. mayoral candidate Rick Caruso, who also built The Grove in Beverly Hills. Glendale’s local politics also reflect the awareness and engagement with their Armenian community. The new mayor, Ardy Kassakhian, is an Armenian-American himself from the area. Glendale highlights the evolution of the identity of the Armenian population in L.A. from small business owners of local Armenian establishments to important leaders, or the “ethnopolitical entrepreneurs” (Fittante 2018) and “ethnic elites” as they enter roles of developers, professors at local institutions such as UCLA and USC, leading lawyers, and doctors.

Glendale maintains a lively Armenian life and solidified its role as an ethnic enclave in L.A. In 2018, the Glendale City Council renamed Maryland Avenue as Artsakh Avenue in honor of the independent territory known as Nagorno Karabakh/Artsakh that has been an area of conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The region recently faced a deadly war in 2020 that resulted in global mobilization among the Armenian diaspora and as expected, the loudest frustration was heard in the Armenian Glendale community whose protestors blocked traffic on the 101 Freeway in Hollywood to bring more media and awareness to this conflict borrowing several tactics from Black Lives Matter protests that were happening just a few months before. The street of Artsakh Ave. includes the Armenian family-owned coffee shop, Urartu, where one can order Armenian coffee known as “hyekakan soorj” and pastries such as “khacapuri.” The coffee shop attempts to recreate a sense of the home for Armenian immigrants with a large wall painting of a monument found in Artsakh’s capital city of Stepankert that is known as “We are Our Mountains” which includes figures resembling a woman and man to represent a grandmother and grandfather (“tatik-papik”).

The City of Glendale has tapped into the importance of emotions and memories tied to place to support the success of an ethnic enclave. As urban scholars have noted, these attachments are critical for creating a sense community and belonging to a place (see Sandoval and Main 2014; Nicholls 2008; Gieryn 2000). Local transnational actors are aware of the global role of Glendale for Armenian-American relations and recognize that large-scale protests such as the blocking of traffic are possible in L.A. The activism in the area highlights how transnational urban social movements are often reliant on their local conditions (Routledge and Leontidou 2010). The Glendale Armenian community is now working on its most recent development with the construction of the first Armenian American Museum and Cultural Center of California that will be located a few blocks from Urartu.

As Glendale continues to develop new Armenian establishments, Armenian-Americans in the area are once again facing potential neighborhood changes as the ability for the city to sustain this ethnic enclave is in question. While Glendale presents a desirable family neighborhood in L.A., housing costs continue to raise thus home ownership is less of a reality for several first-generation Armenian immigrants who have been renters in the area. Instead, several Armenians have looked to parts of “The Valley” such as Sun Valley, Sunland, and Granada Hills as new options for more affordable housing. The movement of Armenians both globally and locally, and their ability to change the places they reside in, illustrates urban theories in practice, primarily that the construction of place is a changing process and never stagnant. When visiting L.A., it is worth spending time in Little Armenia and Glendale to witness the past and present of an immigrant community, and leave with a new appreciation and wonder on where else they will go next. As Fresno’s very own Armenian-American author, William Saroyan, wrote, in what may be considered a transnational poem, “for when two of them meet anywhere in the world, see if they will not create a New Armenia.”

References

- Adar, Sinem. 2018. “Emotions and Nationalism: Armenian Genocide as a Case Study,” Sociological Forum, vol.33(3) pp. 735-756.

- Fittante, Daniel. 2018. “The Armenians of Glendale: An Ethnoburb in Los Angele’s San Fernando Valley.” City & Community, vol. 17(4), pp.1231-1247

- Fittante, Daniel. 2017. “But Why Glendale? A History of Armenian Immigration to Southern California,” California History vol. 94(3) pp. 1-31.

- Gieryn, Thomas F. 2000. “A Space for Place in Sociology,” Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 26, pp. 463-496.

- Nicholls, Walter J. 2008. “The Urban Question Revisited: The Importance of Cities for Social Movements.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 32(4), pp. 841-859

- Paul, Rachel Anderson. 2007. “Grassroots mobilization and Diaspora politics: Armenian interest groups and the role of collective memory,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politic, vol. 6(1) pp. 24-47.

- Routledge, Paul and Lila Leontidou. 2010. “Urban Social Movements in ‘Weak’ Civil Societies: The Right to the City and Cosmopolitan Activism in Southern Europe.” Urban Studies, vol. 47(6), pp. 1179-1203

- Sandoval, Gerardo and Kelly Main. 2014. “Placemaking in a translocal receiving community: The relevance of place to identity and agency.” Urban Studies, vol. 52(1), pp. 71-86.